The Habsburg Cadastral Survey and Map Initiative

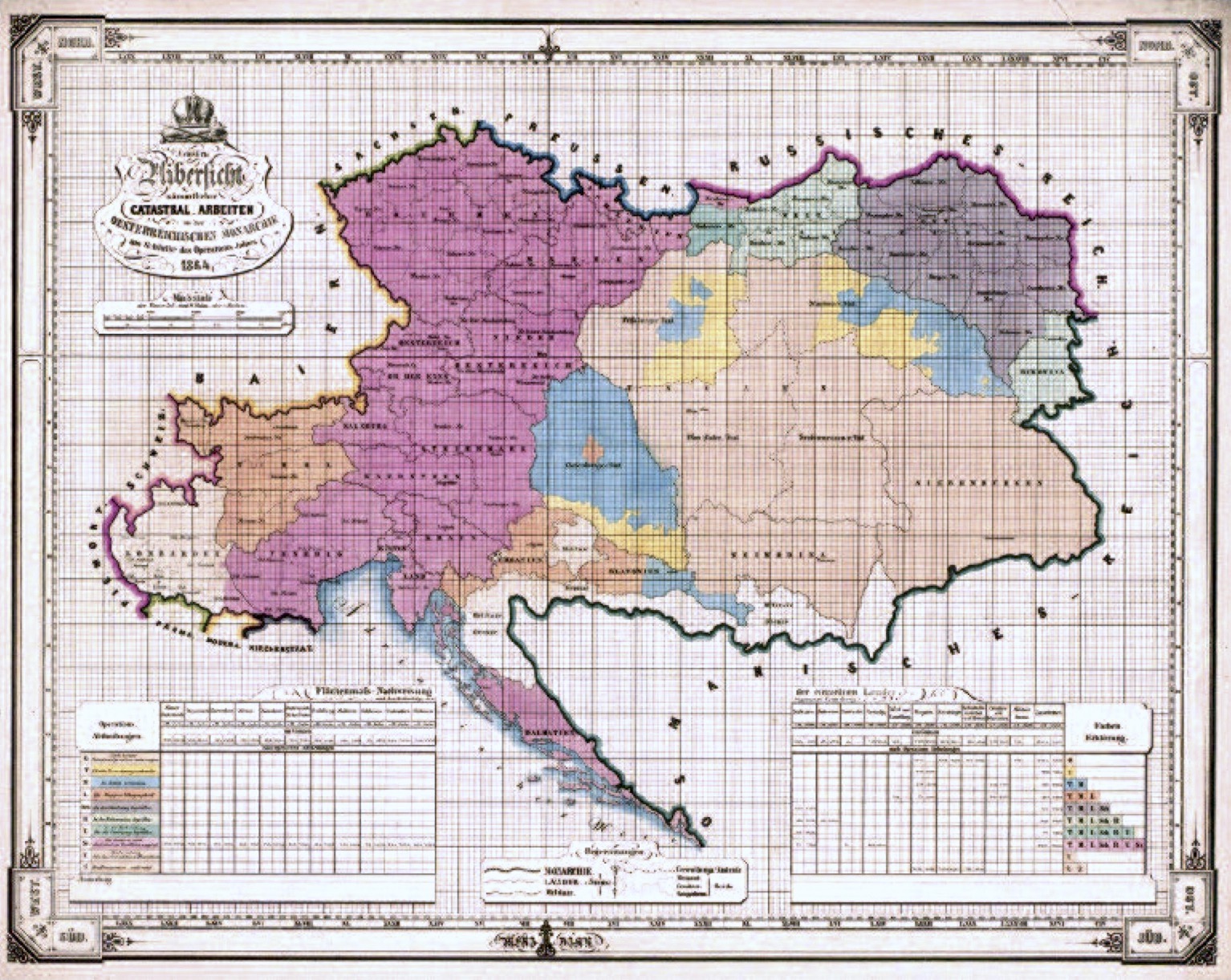

This page of the Gesher Galicia Map Room provides a historical and statistical overview of the cadastral survey and mapping initiative of the Habsburg Monarchy, with special focus on the former Kingdom of Galicia, a territory which now straddles the border between southeastern Poland and western Ukraine. The phenomenal imperial project is traced from its beginnings before the Partitions of Poland which created Galicia, through the first complete surveys and maps in Galicia and the rest of the empire, to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a result of World War I – and into the continuation of the initiative by the Empire's successor states.

Some of the material presented here highlights and quantifies the immense scale of the project, which was both vast and comprehensive unlike any other initiative in the world at the time. Other interesting facets of the project deserving special attention by family historians are detailed on separate pages in the References section of the Map Room.

All of the historical and technical information presented here is adapted from conference papers, journal articles, books, and other texts included among many others on the Reference Literature page in this section, and listed at the bottom of this page. You can read the subsections below in sequence, or click on a link here to go directly to that part of the page:

- Initial Habsburg Land Survey Efforts

- The Stabile Cadastre

- The Scale of the Initiative

- Continuation and Refinement

- References Used on This Page

Initial Habsburg Land Survey Efforts

The Habsburg monarchs were not the first (by far) to survey their lands for valuation and taxation, but they could claim that their efforts led to the first accurate land register on a cartographic basis of an entire country in Europe, and then to significant standardization and propagation of advanced survey techniques for use throughout their vast lands, at internal and external political borders, and beyond. The efforts were primarily based in a need for tax reform across a loosely-aggregated and frequently changing collection of territories united in the person of the monarch. Land taxes were the primary source of funding for the military, necessary to demonstrate power to competing empires to the east and west. Demonstrably fair taxation was necessary to reduce a long history of tax exemptions pushed by the Estates (nobility and clergy) which left a significant burden on the peasant class; leveling the tax basis would both demonstrate Gottgefällige Gleichheit (God-given equality) and help to centralize power.

A century before the first comparable effort in Galicia (and decades before the Kingdom of Galicia was born), first the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI and then his daughter Maria Theresa implemented a land survey and mapping effort of the Duchy of Milan, recently acquired by the Austrian Habsburgs in the first decade of the 18th century. The Milanese Censimento was ordered by Charles VI in 1718 to assess land in this small but wealthy territory. After two demonstrations of the superior survey speed and accuracy of his improved plane-table method, the young court mathematician and astronomer Johann Jakob Marinoni convinced local authorities and work began in 1720 with plane tables, standardized chains and poles, and maps drawn at high scale (1:2000). The full survey, which covered almost 2400 parishes and 20,000 square kilometers, took only about three years. Assessment of land quality and value took longer, and was almost complete when war broke out; the death of Charles VI and political instability further delayed the cadaster, but it finally became law in 1760. Overall it was a greater success of science and mapping than of tax reform, but the example was admired and the methods spread across Europe. Maria Theresa would put her own efforts into leveling taxation across her territories and gathering control into the hands of the monarch, but the benefits of the new survey methods were not forgotten, and her name was attached to the cadastre: il catasto Teresiano.

Maria Theresa's son and successor Joseph II attempted more a significant overhaul of the social and political order, but encountered significant resistance from the Estates and practical problems which limited his achievement. Following a patent (order) of 1785, land survey techniques were simplified so that the peasantry could take up a portion of the work, military surveyors were transferred to support them, and the comprehensive mapping task was largely set aside in order to speed the process; some field sketches were produced to improve assessments, but few were retained after the calculations were complete. Significantly, productive land parcels were numbered and recorded in registers together with the names of the landowners, a key record for later researchers. This "Josephine Cadastre" covered more than 200 thousand square kilometers in four years, including Galicia; it has proven to be very valuable for genealogists and economic historians, but less so for historical geographers. Unfortunately, Joseph's own reform goals were not met; under pressure from the Estates, his brother and successor Leopold II managed in a very short reign to halt the cadastral work and void the reforms Joseph had started.

The incomplete land survey and map collection which Maria Theresa and Joseph II had inherited revealed another weakness: the Monarchy had poor geographical documentation to support their military across their vast territories. Maria Theresa initiated a first complete military survey in 1763 and 1764 in Upper Silesia, Bohemia, and Moravia, which included triangulation for the first time, though imperfectly. The survey continued through the Habsburg territories, in parallel with but separate from the cadastral survey, and into Joseph's reign (giving it the title Josephinische Landesaufnahme or Josephinian Land Survey), eventually completing in 1790; later, a first survey was also made of the newly-acquired (and soon lost) territory of West Galicia between 1801 and 1804. Colorful and detailed hand-drawn topographic maps were produced by military cartographers at a scale of 1:28,800, high enough to show individual buildings without dimensions. The geographical detail of terrain (slopes were indicated with hachures), roads, and rivers plus the corresponding inventory registers of houses, stables, men, and horses was important to the overall goals of the survey to identify potential strategic routes, defensive points, and resources available to the military. The Habsburg Monarchy's first military survey in Galicia was conducted between 1779 and 1783, and is the only historical map series to give a detailed sense of the development of Galician settlements in the early years of Habsburg rule.

Francis II succeeded his father Leopold II as Holy Roman Emperor in 1792 in a time of upheaval in Europe. His aunt Marie Antoinette was beheaded with her husband Louis XVI of France the following year in the middle of revolution and terror in France; the political and military successes of Napoleon pushed Francis to declare himself Emperor (as Francis I) of Austria in 1804 and dissolve the millennium-old Holy Roman Empire, until then the key power in Central Europe, two years later. Also in 1806, Francis directed his Treasury to revive taxation reforms and the imperfect cadastral surveys and assessments which had been idle for almost two decades. As plans evolved for a much more comprehensive (and time-consuming) survey, what was in effect an extension and renewal of the simpler Josephine Cadastre was begun, and even overlapped in time with the beginning of the full survey. This interim "Franciscan Cadastre" again recorded productive land with landowners, using a new parcel numbering system, and often adding a summary of all property holdings for each owner – another useful feature for genealogists and historians, and a measure of the economic development of settlements. As before, no maps or sketches were preserved from the survey.

The Stabile Cadastre

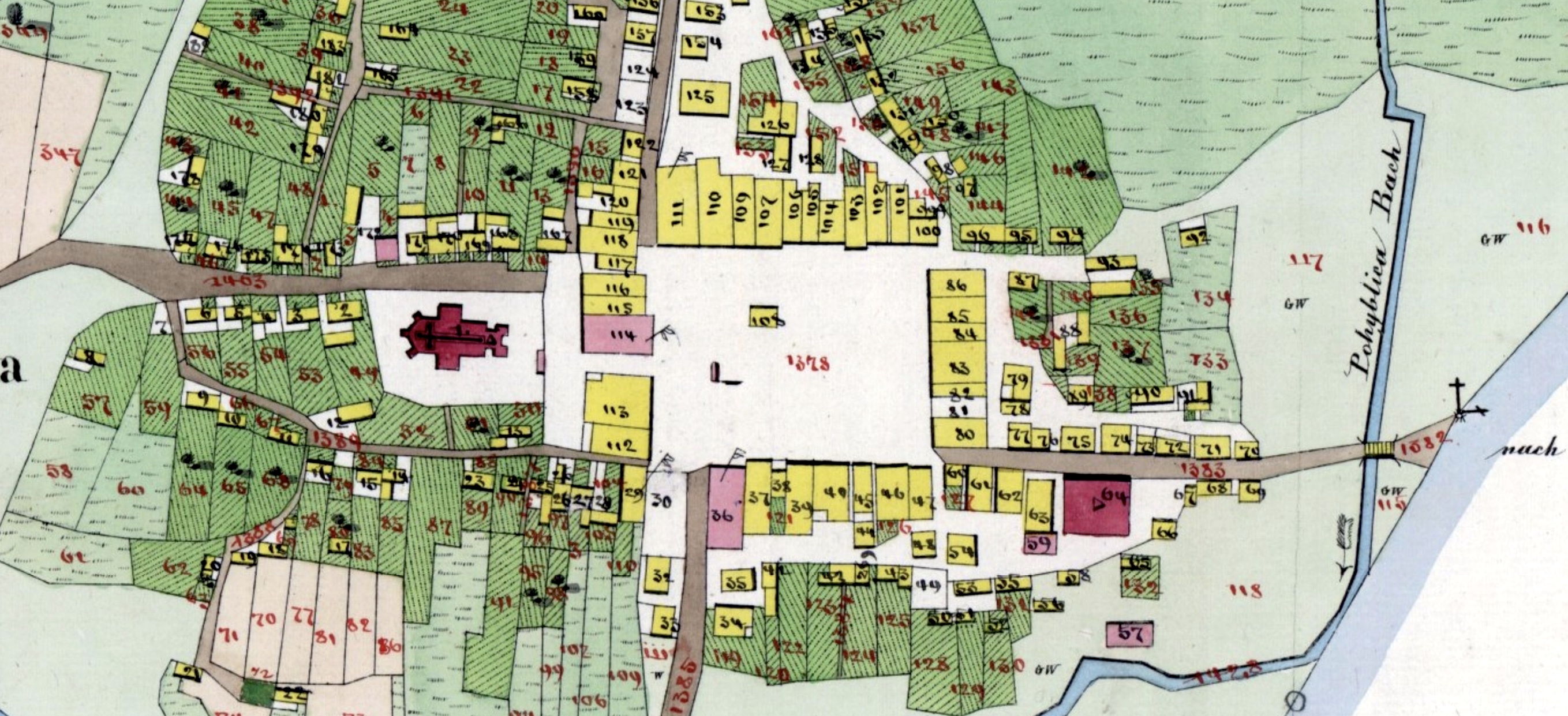

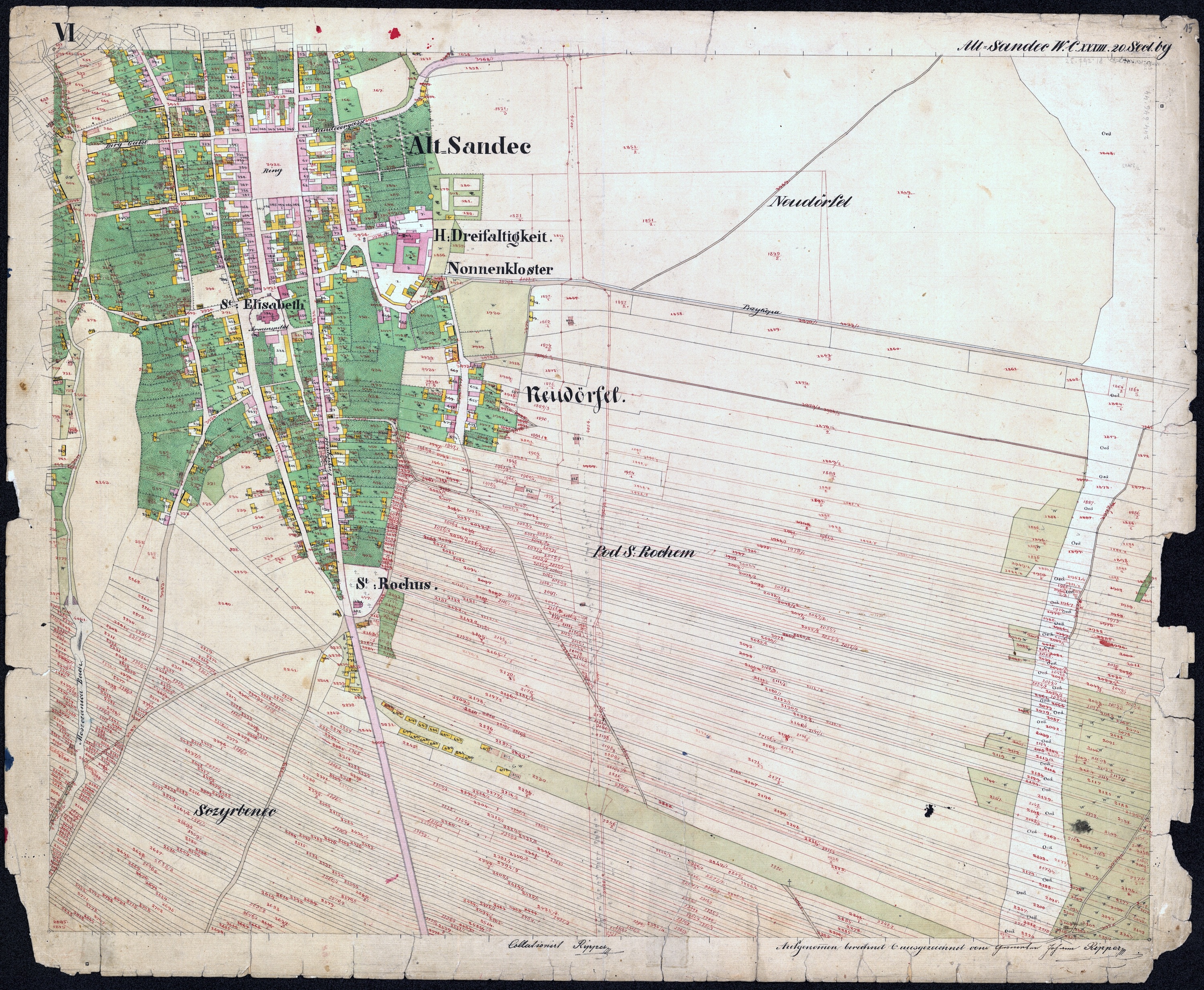

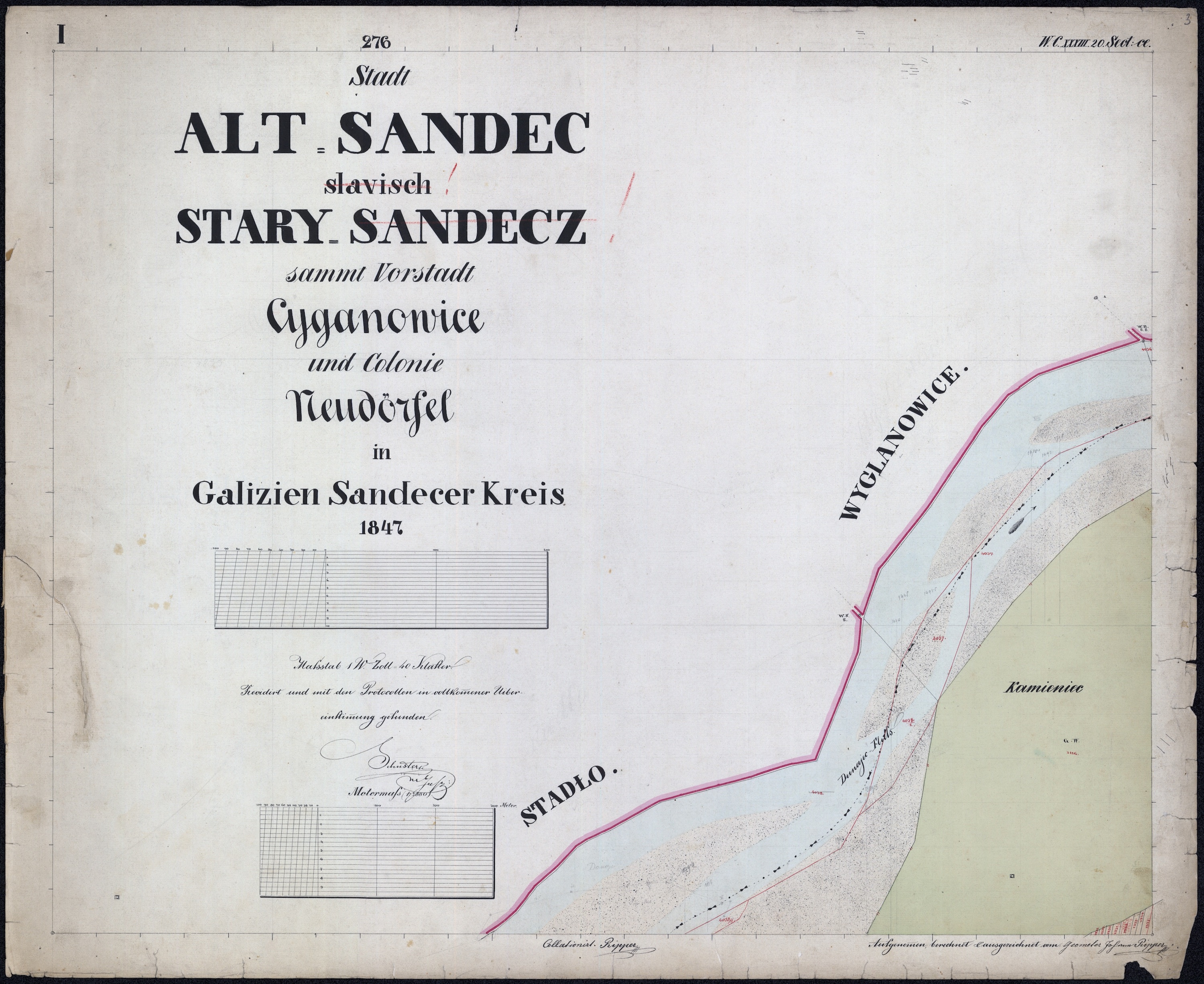

The decade of discussion, trials, and analysis of cadastral survey and valuation methods within Francis's administration led to the imperial patent of 23 December 1817 directing a complete new measure of the entire Austrian Empire. The planning work having already been completed, this "Stabile Cadastre" began immediately in 1817 and completed more than four decades later in the 1861, under the reign of Franz Joseph I; inclusion of Hungary began in 1850, after the revolutions of 1848. In the Gesher Galicia Map Room collection, the earliest cadastral maps of Galicia from the stabile cadastre are based on surveys between 1826-1828. Significant features of the new stabile cadastre included:

- detailed official manuals of instruction guided all aspects of the survey and mapping work; experts and inspectors reviewed each stage of survey and valuation

- all land and building parcels were numbered, measured, valued, and recorded, whether productive or not

- in every cadastral community, a land parcel register (Grundparzellenprotokoll) recorded for each parcel its parcel number, the parcel owner, the land use, and the parcel area in Quadratklafter; similarly, a building parcel register (Bauparzellenprotokoll) recorded for each building (or sometimes a group of buildings on a single parcel) the purpose of the building, its ground area (footprint), the number of stories, the construction material, and sometimes additional details which contributed to the building's value

- parcel valuations were to be "stable" (stabile), i.e. independent of improvements and changes in productivity, effectively rewarding good property stewardship

- the measurements were conducted entirely by professional surveyors using plane tables and standard chains (i.e. the Milanese process); land owners were required to mark the boundaries of their property with stones and/or stakes

- new survey triangulation networks were created to improve and correct the earlier military survey

- all cadastral communities ("tax parishes", which generally but not always matched administrative units) defined in the original Josephine Cadastre were individually mapped, even if small

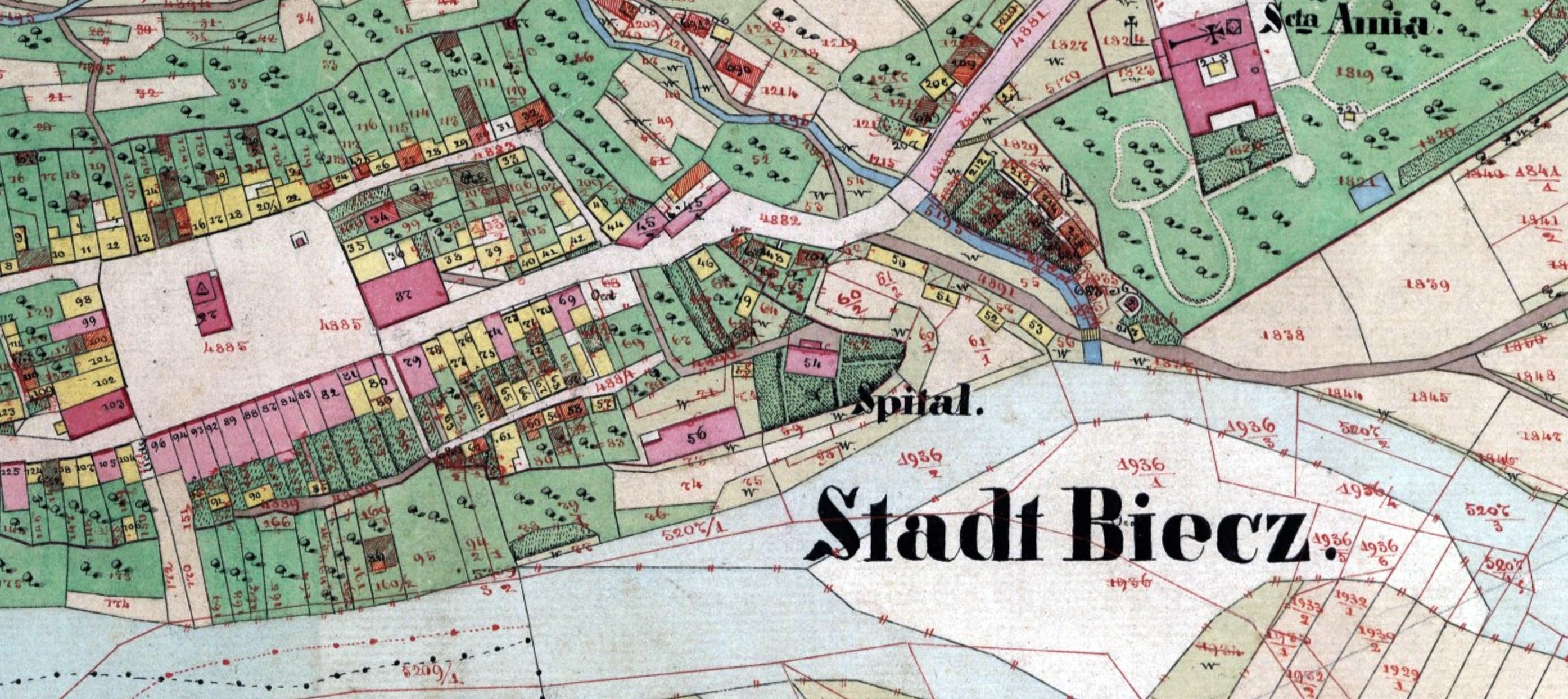

- cadastral maps were drafted at high scale, 1:2880 (i.e. exactly 10 times the scale of the military survey); double- and half-scale maps were created where parcel density or mountainous terrain dictated

- cadastral maps were produced at a specialized institute in Vienna using the recently-invented lithographic printing process for speed and consistency, on sheets of standard size, and hand-colored

- formal cadastral map legends were designed and lithographed to simplify and standardize the inclusion and interpretation of symbols, lines, and colors representing natural and man-made features of settlements and landscapes, the wide range of plantings on agricultural parcels, the materials and inherent value of buildings, and the several types of administrative boundaries

- new archives were created to preserve the cadastral maps and property registers in each of the Empire's separate provinces; a central archive was established in Vienna to store copies of each of the maps

Several aspects of the imperial order and subsequent practical work make clear that the intent was to conduct the new survey for more than tax equalization reasons. The earlier military triangulation network had proven to be defective; the new cadastral triangulation network would serve not only the property measurements but also administrative and military uses (the second military survey, 1807-1870 in the Empire and 1861-1864 in Galicia would use the triangulation and geodetic basis of the stabile cadastre and a subsequent military net). Precise geographic depictions of roads, rivers, forests, and more on the detailed maps likewise served military needs for strategic planning. The high-scale cadastral maps, while too cumbersome for carrying into the field for administrative and military use across larger regions, could be rapidly reduced either mechanically with pantographs or mathematically in new map production.

The Scale of the Initiative

Researchers who use this website are accustomed to studying individual Galician cadastral maps in close detail, to virtually walk through a historical town to better understand where ancestors lived and learn clues about their economic status, the character of their neighborhoods, where religious community resources were located, and much more; this is history on a human scale and point of view. However, sometimes it can be interesting (and astounding) to zoom out and study the Habsburg initiative at a macro scale, across the Kingdom of Galicia and higher: across the entire Austrian Empire. Zooming back in, it can be astonishing to appreciate the fine detail of the surveying and mapping project, and how the administrators defined "comprehensive" in their work. Remarkable statistics of the now 200-year-old initiative have been provided by the organization which inherited the cadastral task for Austria's future, the Federal Office for Calibration and Surveying (Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen, BEV), and other map historians have provided additional information of interest and value.

Some numbers:

- Land Area: at the start of surveying for the Stabile Cadastre, the Austrian Empire covered roughly 300,000 square kilometers, about the size of modern Poland; at its peak size the entire diverse Austro-Hungarian Monarchy covered roughly 640,000 square kilometers

- Cadastral Map Sheet Size: at the high scale of 1:2880 used almost uniformly through the measuring and mapping process, nearly all cadastral communities / towns required several map sheets for full coverage; one standard map sheet at 66cm by 53cm thus covers an area of about 1800m by 1500m, or about 2.75 square kilometers; the irregular shape of cadastral communities and their random spatial alignment with the geodetic grid, plus the need for clear border labeling, titles, etc., significantly contributed to the total number of required map sheets

- Cadastral Map Sheet Count: with the spatial needs for borders and titles, the Austrian Empire required more than 160,000 map sheets; by itself, Galicia required more than 40,000 map sheets (Galicia was the largest crown land in the Austrian Empire)

- Property Parcel Count: the estimated number of parcels identified and numbered, with their borders measured and mapped, and their contents valued across the Austrian Empire was about 50 million individual land and building parcels

- Map Detail Resolution: the high scale of the maps consumed a lot of paper but also permitted significant detail to be captured with precision; the typical fine line widths on lithographed cadastral maps correspond to a distance on the ground of less than 0.5 meter

As noted above, the Stabile Cadastre took 44 years to complete (in Galicia alone, the work proceeded from 1819 to 1854, or 35 years), and in the process created an accurate and effective empire-wide geographical information system. Historians have noted that the survey measurement, mapping, and administrative teams worked six days per week, from sunup to sundown, throughout this time.

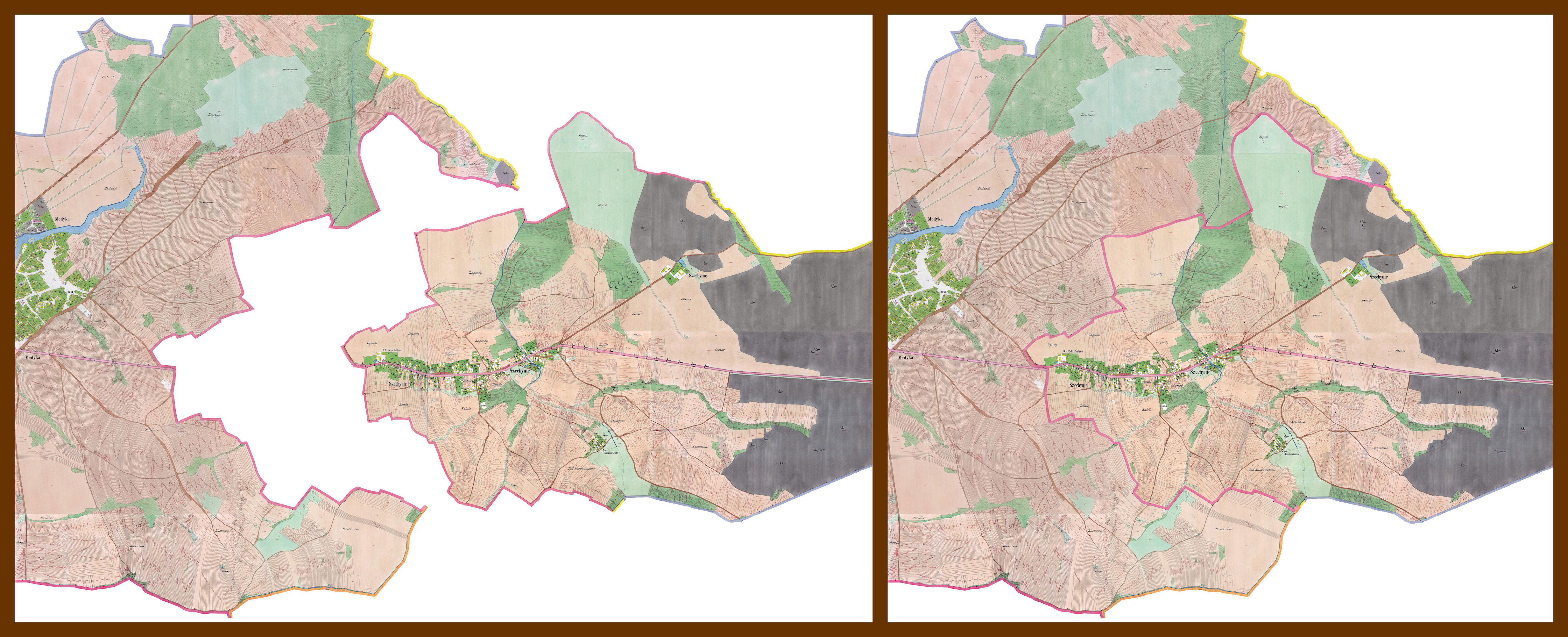

We have also highlighted that every parcel was documented, even those considered unproductive, barren, or "wasteland" (Ödland, often abbreviated Oed.), and we have noted that cadastral communities were contiguous, without gaps and without or overlaps (except where strips of land were legally contested between adjacent communities and the dispute was recorded on the maps). This means that virtually every square meter of land was measured and mapped during the cadastral survey, and some information about its contents was recorded both visually on the maps and in text form in the property registers. Hundreds, even thousands of examples of the tight fit of individual parcels are visible on every historical cadastral map. Complete mapped cadastral communities fit together like pieces of a complicated jigsaw map. One example is shown below, at the east-west boundary between the towns of Medyka and Szechynie (today Medyka and Shehyni face each other across the Poland-Ukraine national border). In the left panel, composite graphical assemblies of several sheets for each town are placed next to each other to highlight the mating borders; in the right panel, the two separate maps are placed together at their joining edge, showing how no gaps remain. This same attention to detail and record-keeping drove the entire Stabile Cadastre process.

In the left panel, the maps for the adjacent cadastral communities are shown separated to illustrate how the community boundaries tightly conform at their border. In the right panel, the maps are shown together (as on the ground), with no gaps at the magenta-colored boundary.

The Habsburgs were not unique in Europe at the time in their desire to comprehensively measure and map their lands, nor were they the only government with access to skilled scientists and cartographers, but the Austrian initiative stands out for its quality. France, a far less diverse country of comparable size where revolution and regicide were driven partly by unfair taxation, conducted a similar full cadastre across all of its territories beginning at nearly the same time as in the Austrian Empire, and proceeding at a similar speed, but the resulting individual maps were not carefully tied to the national triangulation net, and the survey and valuation results were not subject to inspection; upon review, a portion of the survey was considered defective, and the first full French cadastre did not stand as a legal database.

Continuation and Refinement

The statistics quoted above lack a key dimension which dramatically amplifies their size: time. Nothing in the Austrian and Austro-Hungarian Empires was static over years and decades, even if the rough outline of the empires was reasonably constant until World War I. The "stabile" cadastre was meant to hold property valuations for taxation steady, but on their lands property owners and both civil and religious communities cut and developed roads, dammed creeks and rivers to create reservoirs, dug canals, split and joined parcels, and especially built new structures, both residential and commercial. Some towns suffered wide-spread fires. Already from the 1840s in Galicia, railways cut sinuous lines through the landscape, protected by rights-of-way and embellished by stations, stores, and bridges. New cemeteries were established, old prayer houses of wood were replaced with finer structures in stone. Mills, breweries and distilleries, quarries, brick factories, and military barracks and training grounds were established. In addition to changes in property profiles, survey technology and practice also evolved and improved after the start of the survey.

By the completion of the stabile cadastre, some of the survey data and much of the land valuation pricing scheme were obsolete. A new survey was ordered by Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1869 to regulate the land tax and to prepare new maps where significant changes had occurred since the Stabile survey, and importantly, to mark existing and new triangulation points on the land. In practice, this updating and refinement of the land survey continued to the end of the imperial era.

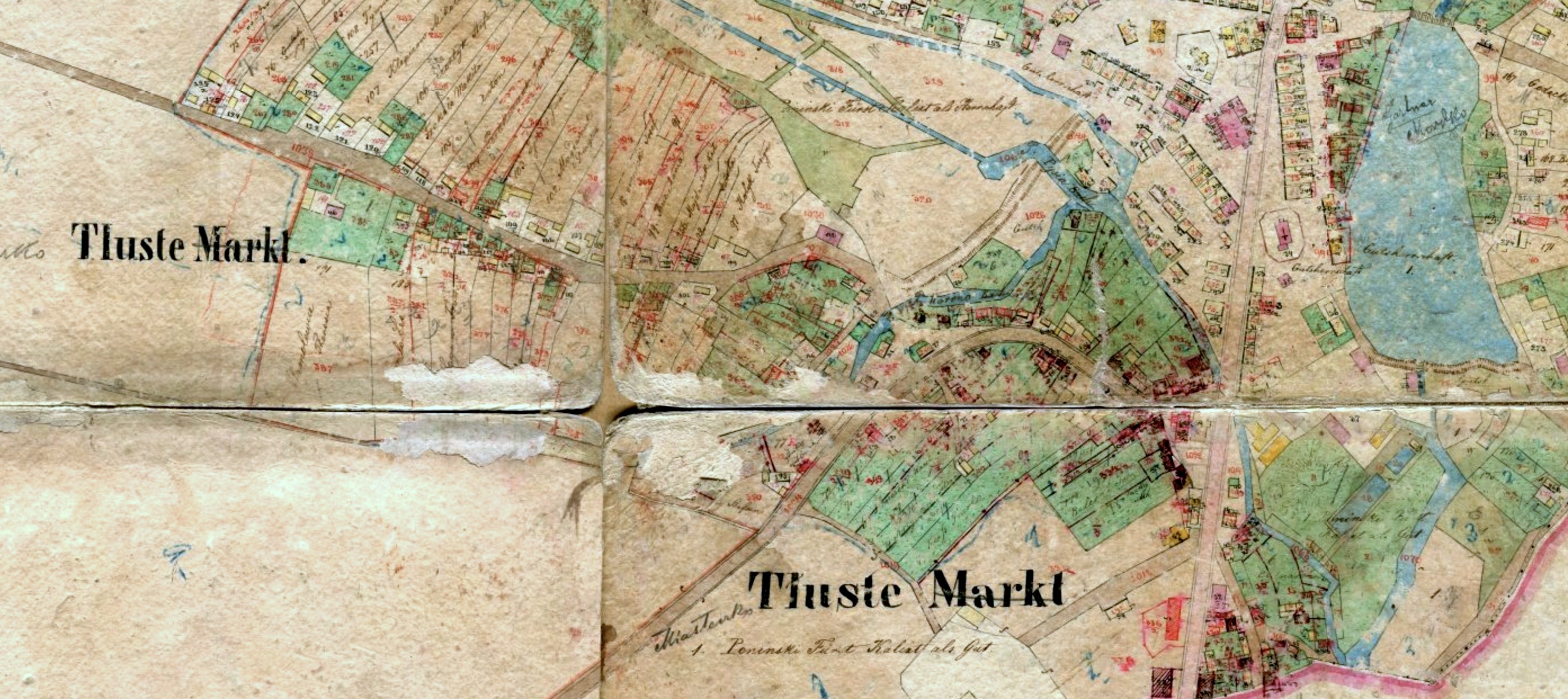

But even before formal order for a new survey, the quality assurance scheme of the prior Stabile cadastre effectively provided for ongoing updates. As a final step to the survey, mapping, and documentation process, commissioned expert inspectors reviewed the maps on the ground, by walking, measuring, and checking the information. Many cadastral maps of Galicia from the 1840s and 1850s include the word Revidirt (Revised) in the title block. Some towns which were originally surveyed in the 1820s appear in later maps from the 1850s and early 1860s with the title annotation Reambulirte Auflage (Reambulated Edition), i.e. based on a "re-walking" survey.

Other cadastral maps in the Gesher Galicia collection show even more significant evidence of field revision work. For reasons unknown, a large percentage of the maps, especially from eastern Galicia (i.e. preserved in western Ukrainian archives) had each sheet folded into quarters and sometimes even cut at the folds and glued to backing boards, presumably so they could be easily carried and marked while walking and inspecting to evaluate the maps for accuracy and to record changes since the original survey. These maps usually include a large number of red-line revisions, often showing land parcel divisions and new building additions. All of these vestiges of the immense cadastral survey initiative record signs of a kingdom and an empire in constant flux.

References Used on This Page

The Reference Literature page in this section provides a large number of conference papers, journal articles, books, and other texts relevant to the history of the Habsburg cadastral survey and mapping initiative. The following references were especially useful in assembling this page:

- Roger J. P. Kain and Elizabeth Baigent, "The Cadastral Map in the Service of the State – A History of Property Mapping", University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Susanne Fuhrmann, Digitale Historische Geobasisdaten im Bundesamt für Eich- und Vermessungswesen (BEV) Die Urmappe des Franziszeischen Kataster (Digital historical geobase data in the Federal Office for Calibration and Surveying (BEV): The original documents of the Franciscan Cadastre), BEV, 2007.

- Susanne Fuhrmann, The Historic Cadastre 1817 – 1861, Icarus Cadastral Maps Network initial meeting, Budapest, 2010 (published 2012).

- Brian J. Lenius, "Cadastral Land Surveys and Maps for Galicia, Austria"; East European Genealogist, Spring 2005, Volume 13, No. 3.

- Victor O. Buyniak (trans.), "Preface to The Josephinian (1785-1788) and Franciscan (1819-1820) Cadastres"; East European Genealogist, Winter 2021, Volume 30, No. 2.

- John D. Pihach, "Examples and Analysis of Entries from the Josephinian and Franciscan Cadastres"; East European Genealogist, Winter 2021, Volume 30, No. 2.

- Rumpler, et al., Der Franziszeische Kataster im Kronland Bukowina Czernowitzer Kreis (1817–1865): Statistik und Katastralmappen, Böhlau Verlag, 2015.

- Andrew Zalewski, "Early Galician Population Surveys: Hidden Genealogical Gems"; The Galitzianer, March 2016, Volume 23, No. 1.

- Andrew Zalewski, "Research Project Updates: Josephine and Franciscan Surveys Project"; The Galitzianer, September 2017, Volume 24, No. 3.

- Franziszeischer Kataster (Franciscan/Stabile Land Survey) (in German)

- Katastral Vermessungs Instruktion 1820 (Cadastral Surveying Instruction 1820), BEV, no date [1820].

- András Sipos, "Cadastral Maps – Ideal Field for International Archival Cooperation", paper presented at the ENArC/Icarus workshop "Cartography and Cadastral Maps: Visions from the Past, for a Vision of Our Future", SNS Pisa Italy, 2013.

- Using Cadastral Maps of Galicia, From Shepherds to Shoemakers (blogsite), 26Sep2018.